BACKGROUND

On June 26, 1960, Somaliland formally declared its independence from the United Kingdom. Shortly thereafter, on July 1, 1960, the State of Somaliland and Italian Somalia united to become the Somali Republic. However, Somaliland regained its independence in 1991 after years of struggle, spearheaded by the Somali National Movement (SNM), a guerrilla movement predominately comprised of people from the Isaaq clan that fought against the Somali regime led by President Mohamed Siad Barre. Under Siad Barre, the 1988 bombing of the important Isaaqi cities of Hargeisa and Burco led to the systematic killing of thousands of civilians. The story of Somaliland’s independence, which was proclaimed in 1991 after the fall of the Somali state, is heavily influenced by this horrifying incident of state-sponsored genocide against the Isaaq people.

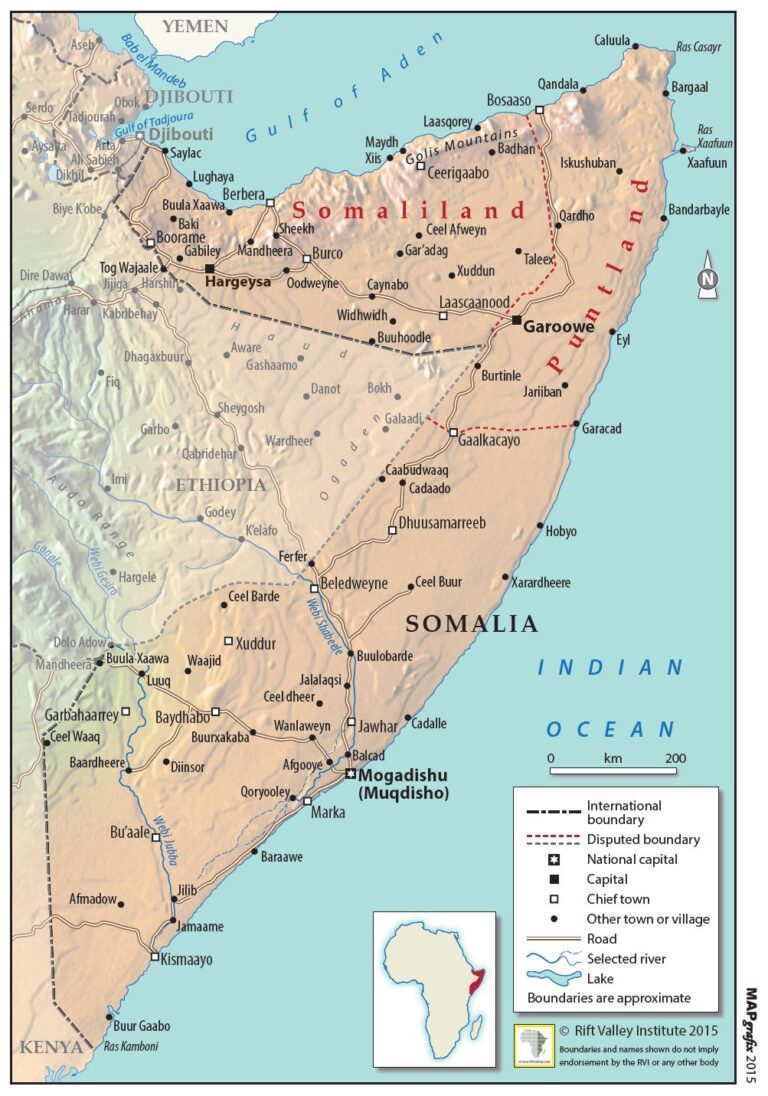

Throughout the last three decades, Somaliland’s identity has been firmly linked with the Isaaq clan. While the Isaaq people predominantly live in Somaliland’s central regions, Somaliland claims the former British Somaliland protectorate’s territorial boundaries, which includes members of other clans such as Dhulbahante, Gadabursi, Warsangeli and Issa. While Somaliland identifies itself as a state based on the criteria for statehood in the 1933 Montevideo Convention on the Rights and Duties of States, Somaliland has not received de jure recognition from the international community. Despite the lack of recognition, Somaliland has moved forward in a post-civil war peace and state-building process without outside interference in its political process and has managed to maintain a level of stability despite the significant instability that has continued in Somalia.

THE CONFLICT

Las’Anod (Laascanood in Somali) is the capital city of the Sool region, which is estimated to have a population of over 300,000 people, the majority of whom come from the Dhulbahante clan. The Sool region is claimed by both Somaliland – a de facto state – and Puntland which is part of the Federal Government of Somalia (FGS). The justification for Puntland’s claim to Sool is based on a genealogical logic as the Dhulbahante clan is a sub-clan of the clan constitutes the majority in Puntland, whereas the Dhulbahante clan represents a much smaller share of the population in the rest of Somaliland, relative to the Isaaq clan. In October of 2007, Somaliland forces took control of the city of Las’Anod from the Puntland government. In the 16 years since Las’Anod became part of Somaliland, the city has experienced relative peace and some economic development. However, throughout this period a strong military presence has remained in place at the peripheries of the city. As the region is at the edge of an area claimed by both sides, there has long been the presence of the military of Somalia in Garowe and of Somaliland on the outskirts of Las’Anod. This situation has undoubtedly created some level of tension in daily life. In a focus group discussion, women from Las’Anod shared that they feared the Somaliland soldiers, citing examples of being threatened by them, specifically that women working as vendors in the market were verbally abused if they were unable or late to pay their taxes.[1]

Las’Anod has had a series of targeted killings of notable individuals, including politicians and academics, totaling over 100 deaths since 2009. The most recent was Abdifatah Hadrawi, a well-known member of the major opposition party (WADANI) in the Somaliland political system, who was assassinated in December 2022. As has been the case in most of the previous murders, his assassins were never caught or arrested. These assassinations have been shrouded in doubt as governance and law enforcement from Somaliland and Puntland have launched contradictory allegations of guilt. Clear answers surrounding the perpetrators of the killings have remained elusive. To the Somaliland administration these killings are the results of terrorist groups coming from Somalia, and thus there has been a lot of rhetoric supporting securitization and heightened militarization in the area. Indeed, hundreds of families were deported from Las’Anod in early October of 2021 following one of these murders. On the other hand, in Puntland, the claim is that these killings are evidence of clan-based tensions, and that the people are targeted for being part of the Dhulbahante clan. The Puntland government thus positions itself as a protector of a people who are genealogically tied to Puntland much more so than to Somaliland. Now with the bombing of Las’Anod, some have gone so far as to say the Isaaq-dominated Somalilanders are using this conflict as a means to take revenge for the genocide against the Isaaq people that occurred almost 35 years ago.

In the wake of Hadrawi’s murder, frustrated residents, the majority of whom were women and young students, called for protests to demand justice. Ten to fifteen civilians were killed or seriously injured when police and military opened fire on the demonstrators. In early January 2023, the Somaliland military was told to withdraw to its bases just outside the city, but the protests increased, and some burned the Somaliland flag, while hoisting the flag of Somalia. The whole month of January was characterized by ongoing clashes between the Somaliland forces and the local militia. Businesses were closed due to the daily demonstrations and clashes. Doctors report that hospitals have been shelled. Women in the focus groups reported that the shelling caused interruptions in access to electricity, water, and that the stores/markets were closed.[2] In response to the situation, a committee of 33 members was formed by local traditional Garaads, however not a single woman was included in the committee. In early February 2023 the committee announced their allegiance to the Federal Government of Somalia and demanded that the Somaliland armed forces leave their land.

On February 7, 2023, members of the international community gathered to issue a statement calling attention to the gravity of the situation and pleading for “an immediate de-escalation of violence, the protection of civilians, unimpeded humanitarian access and for tensions to be resolved peacefully through dialogue.” Unfortunately, the situation worsened, and the International Community, FGS and UN Security Council successively called for a cease-fire and de-escalation. However, the fighting between the local militia and the Somaliland armed forces intensified.

Under these conditions, the population started fleeing the city of Las’Anod to the surrounding villages and once these locations were deemed unsafe, the civilians fled to over 11 cities/districts primarily in the Puntland region, but also as far as Jigjiga in Ethiopia. The largest concentration of people displaced by this violence is currently in the city of Garowe.[3] More than 185,000 people have been displaced from Las’Anod, according to an inter-agency assessment mission, and around 89% or 164,650 of the displaced are women and children.[4] Hospital staff in Las’Anod have reported that at least 145 had been killed and another 1,080 had been injured as 4th of March. A key informant from another hospital in the region reported that at least 12 of the slain were women and 25 were children (younger than 18).[5]

To understand the gendered impact of this currently evolving situation, we conducted 9 key informant interviews and 3 focus groups discussions with women from Las’Anod and from civil society in the area.

THE IMPACT ON WOMEN AND GIRLS

The marginalization of Somali women in all spheres of life is evidenced and perpetuated by their absence from socioeconomic and political decision-making, the widespread acceptance of cultural and religious justifications for their oppression, and the lack of value placed on their lives. Peace processes that are forged without the meaningful participation of women cannot claim to be fair or representative and are typically short-lived. The widespread exclusion of women from leadership roles before, and after conflicts only serves to exacerbate their victimization as women are trapped in a vicious dilemma: despite being the primary civilian victims of conflicts, they are excluded from the negotiations during the resolution and reconciliation processes. Despite the fact that women initiated nonviolent riots against the Somaliland government and forced them to the negotiating table, no woman was allowed to join the 33-member committee of the Garaads.

The structural, institutional, and cultural barriers that impede women and girls’ access to income, wealth, resources, and decision-making roles leave them especially vulnerable to the traumas and difficulties that accompany conflict-driven displacement. The lack of access to basic services such as healthcare and education can have long-term effects on their well-being and future prospects. Unfortunately, these access barriers are often compounded by social and cultural factors, making it even more challenging for internally displaced women to receive the support they need or the independence to walk away from unsafe or exploitative circumstances.

Most of the women and girls displaced by the Las’Anod conflict are living in precarious and dire situations, some are living in makeshift shelters in the open and or under trees despite the rain, wherein their basic needs are not being met.[6] Focus groups participants had heard of pregnant women giving birth in extremely harsh conditions.[7] In these circumstances, access to education has become severely compromised. An OCHA Report has estimated that 345 institutions have been closed, 54,000 students are out of school, and 2,045 educators are out of work as a result of the conflict in Las’Anod. Being out of school, also makes girls much more likely to be forced into marriage, which combined with the economic hardship facing the displace, many families are likely to turn to child marriage as a means to stay afloat, placing girls into life of constant risk of physical and sexual abuse. Young, orphaned girls are particularly vulnerable in this context and are thus most likely to be forced into nonconsensual marriages, and exploitative or unsafe labor. These practices not only perpetuate the cycle of poverty but also put women and girls at a higher risk of physical and emotional harm.

Another element that genders the hardships of displacement comes from the norms around marriage, child custody, and land ownership and their intersection with clan identity. For example, when couples marry, the woman moves to the area of the man’s clan. This dynamic, places women in a vulnerable position because when clan-identity is involved in a conflict – even if it is not the root cause or primary focus of the conflict – women are at risk of losing their children. As child custody is given to husbands by default, the husband and the children will be from the same clan and can seek the support and refugee of their other clan members and their clan lands (lands in the Somali region are typically controlled by clan not government). Women, on the other hand, are at risk of being associated with the ‘enemy’ since they are not originally from the same clan as their husband and children, and thus can be cast out without any recourse or means to seek child custody. Another layer of this vulnerability manifests in practices around land ownership and clan identity. Even when a woman inherits or owns land, as soon as she marries a man, her land becomes his land, and if he is from another clan, the family of the woman will typically first take the land from her so that it does not go to the man’s clan. This practice means that women in Las’Anod are much less likely to have access to lands they can flee to in order to take refuge. These issues are far worse for women from a minority clan like Gaboye, as this clan does not have any region, town, or area of land that is owned by the clan, and thus these women have no where to flee to. Moreover, the militias in Las’Anod are clan-based, but there is no militia in the Sool region for the minority clans, and thus women and girls from these clans will not fall under the protection of either of the sides in this conflict.

Personal account from a displaced student:

The day after Hadraawi was killed, I went to school to write my exams. After we were done, a large group of students – myself included – decided we needed to stand up and demand justice for the men that were assassinated and did not receive justice. When we gathered and started shouting and demanding for justice, we were met with gunshots from the Somaliland forces. We started throwing stones at the armed forces and that is when they started shooting into the crowd. I witnessed the killings of my classmates, friends, and neighbors. I ran away in shock and horror. They were shot by specially trained sniper forces.

The deaths of my friends did not stop me from demonstrating and throwing rocks. However, when the bombings started, when the hospital near our home was bombed, when our home was destroyed, I became very afraid and terrorized. We found ourselves unable to leave our homes. We had no power, no water, no food, no telephone service and no internet. All we heard was constant gunfire and bombings. Our family stayed in Las’Anod until February 22, 2023. We fled our home and city on foot with only the clothes we were wearing on our backs. We walked for miles as we saw our city burning and being destroyed. I do not wish this kind of experience even for my worst enemy. I had never experienced bombings before this experience. My mother, my siblings and I are now in Garowe homeless, living with uncertainty. We do not go to school. I want a peaceful resolution to the conflict, but I feel it can only become reality if the Somaliland forces leave our land.

While sufficient data is very difficult to access, a key informant from civil society in Somaliland reports that the organization has documented 28 cases of rape of women and girls in Las’Anod by armed men – either from the local clan militias or from the Somaliland armed forces. As increased cases of SGBV are often when conflicts break out, it is likely that the cases will continue to rise if immediate action is not taken to support survivors, pursue accountability, and de-militarize the situation. Indeed, UNSCR 1325 recognizes that wars and armed conflicts have gendered impacts. The resolution urges warring parties to recognize and uphold women’s rights, by not engaging in any form of gender-based violence. This includes measures to prevent sexual violence, ensure access to justice for survivors, and provide support and services to those affected by violence.

Humanitarian partners must prioritize addressing the unique needs of women and girls in displacement situations. This includes providing access to basic services, creating safe spaces for women to come together and support each other, and implementing programs that empower women and girls to rebuild their lives. Women’s voices and experiences should not be represented by men who speak on their behalf; instead, women must be directly consulted. The meaningful involvement of women and girls in the design, implementation, and monitoring of humanitarian responses is critical. When women are fully engaged, it can lead to more effective and sustainable solutions that are responsive to the unique needs of women and girls. Overall, gender equality and the empowerment of women and girls are essential components in achieving inclusive, effective, and life-saving humanitarian action and lasting transitions to peace.

The women of Las’Anod have been pushed to the sidelines of the resolution for too long. Women-led organizations have received significant training to implement the pillars of the UNSCR 1325 in line with the needs of their state. Now is the time to make use of that capacity, by engaging women-led organizations, which are already at the forefront of peace efforts for Las’Anod, albeit in informal ways. The focus group discussions clearly identified that women have been and want to continue playing a part in the resolution of the conflict. In particular, the younger women that believe in their right as citizens to actively participate in the political resolution. Therefore, their energy, passion and hopes for a better future need to be channeled alongside local women-led organizations.

RECOMMENDATIONS

Women want to return home and believe that the only way forward is to:

- Establish open peace talks, where women from all backgrounds are able to access the negotiations and have a seat at the decision-making table – this necessitates a change from the status quo, in which women are excluded from the 33-member committee.

Therefore, the question now is, how can this way forward be achieved:

- Coordinate an urgent call for an enforced ceasefire and removal of troops by engaging regional and international institutions in line with peace and security.

- Engage peace talks through a coordinated effort, with support from the international community under the women, peace and security agenda of UNSCR 1325.

- Ensure that women are a key component of the peace talks by bringing in women-led organizations that represent the women of the region.

- Increase funding for the host community of Las’Anod to cover urgent health, WASH and nutrition gaps.

- Inject funding into IDP communities from Las’Anod situated in Garowe to provide urgent psychosocial, health, protection and shelter support. Keeping in mind that these women want to return to their homes and be part of the political resolution, empowering them the immediate rehabilitation services they might need to be part of the peace-keeping process moving forward.

[1] March, 2023. Focus Group Discussion (FGD) with women in Las’Anod.

[2] March, 2023. Focus Group Discussion (FGD) with women in Las’Anod.

[3] March, 2023. Key Informant Interview who wished to remain anonymous.

[4] February 14, 2023. OCHA Somalia Flash Update No. 2 Fighting in Laas Caanood, Sool Region

[5] Key Informant Interview March 23, 2023. Dr. Ibrahim Elmi Obsiye, Manhal Hospital, Las’Anod, Sool

[6] March, 2023. Key Informant Interview – Interview from within Puntland Humanitarian Aid Committee for Las’Anod (based in Garowe).

[7] March, 2023. Focus Group Discussion (FGD) with women in Las’Anod.

Writing and Publication: SIHA Network

Published: March 2023

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reprinted or reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means electronic, mechanical or other means now known or hereafter invented including copying and recording, or in any information storage retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

Strategic Initiative for Women in the Horn of Africa

PO Box 2793 Kampala – Uganda

www.sihanet.org

©SIHA Network 2023